Dr. C.V. Alert, MB BS, DM. FCCFP.

Family Physician.

When faced with a challenging situation, there are two basic options: attempt to tackle the problem, or turn your back on the problem and hope that miraculously that the problem will disappear. In political terms this latter is often termed ‘kicking the can down the road’.

A recent WhatsApp video circulating in Barbados highlighted a situation where someone had to wait three to four days in the Accident & Emergency Department (A&E Department) of the Queen Elizabeth Hospital, our only Tertiary Care Level hospital, before being seen by a physician. The response by the acting Minister of Health was that the official investigation suggested that the average waiting time was closer to 30 hours (‘only’!). The acting Minister then went on to describe the triage procedures in the A&E Department, and also suggested that (some) persons who presented to the A&E Department would be better served by going to their polyclinics (local health centers).

(Some) potential patients are quick to point out that, when they attempt to go to their local polyclinics with an acute problem, they are offered an appointment to see a physician in a few weeks (sometimes even longer) time. This has led to a proliferation of Emergency Clinics in Barbados, but these are mainly fee for service clinics, outside of the pocket range of many persons, especially in a population with a growing number of elderly persons, many of them reliant on relatively static pensions to survive in an environment where prices are continually rising.

The result: many persons can’t access medical care in a timely manner, their disease states are allowed to incubate and fester, and eventually, when seriously ill and sometimes on death’s door, they are forced to go to the A&E Department. The medical reports coming out of the A&E Department are that more and more seriously ill patients are presenting for medical care, leading to overcrowding of both the A&E Department and also the hospital wards. In 2020 the CEO of the QEH noted that the bed occupancy of the medical wards in the QEH was 200%. The annual report of the CMO in the Ministry of Health for 2006 gives this figure as 120%, showing that this problem has been going on for many years now, and that ‘kicking the can down the road’ in 2006 has, so far, not produced any results that suggests that this process is improving; in fact most available evidence suggests that things are getting worse. [At this point in the 2006 report, the Chief Medical Officer (CMO) of the Ministry of Health noted that “This (bed occupancy) information suggests that secondary and tertiary care management of chronic diseases is consuming an above average proportion of the resources of the QEH. Therefore, new evidence-based strategies for managing these diseases should be implemented with utmost urgency.” Although the CMO used the phrase “with utmost urgency”, to this point 17 years later this has not happened. The can continues to be kicked down (what may possibly be) a very steep road].

My ‘two-cents suggestion’, mentioned repeatedly over the years and supported by the data from other countries, and also taking into account that good primary care is a lot less expensive than Tertiary care, has been we need to focus on improving our Primary Care, i.e., the quantity and quality of care available in our polyclinics. Our local medical research, such as the Health of the Nation study in 2015 – a national study that evaluated the health of 1234 adults aged 25 years and over – found that diet and exercise habits were poor, overweight and obesity were rampant, and physicians (in primary care) struggled to control hypertension and diabetes in a majority of persons who developed these diseases. These poor health habits are not treated with Cat Scan, MRI or X-ray machines, and do not need to be lying down on a hospital bed with a bevy of nurses around you. The complications of these diseases include heart attacks, strokes, renal (kidney) failure, all conditions that must be treated with expensive tests, investigations and medications, in a high cost Tertiary Level Institution: our health services is allowing us to generate many patients who end up needing such care.

So instead of focusing on “Health Promotion and Disease Prevention” and improving the primary care services that our research has shown to be deficient, our Health Planners have focused on expanding the A&E Department and Emergency Services; we lament that we cannot (easily) afford a new state-of-the art bigger and better Hospital; we have established a Stroke Unit at the QEH ( with 6 beds, while in Barbados we average 6 strokes every 4 days, so we will have no shortage of persons waiting for a bed in this high-tech unit); we have a Cardiac Suite to cater to the ‘heart attack a day’ that we currently generate; and our Ambulatory Kidney Unit (AKU) costs us millions to run while only being able to treat a fraction of the patients that need dialysis or a transplanted kidney. Improved primary care offers us the opportunity to lower (but not completely eliminate) the numbers of patients that need the expensive Tertiary Care, or that fill up the A&E Department and our hospital wards.

The analogy is this: if your tap is leaking and the floor is getting wet, you can either attempt to fix the leaking tap or buy an expensive set of mops to keep the floor dry. Primary Care medicine attempts to stop the leak, while Tertiary Care medicine attempts to mop the floor.

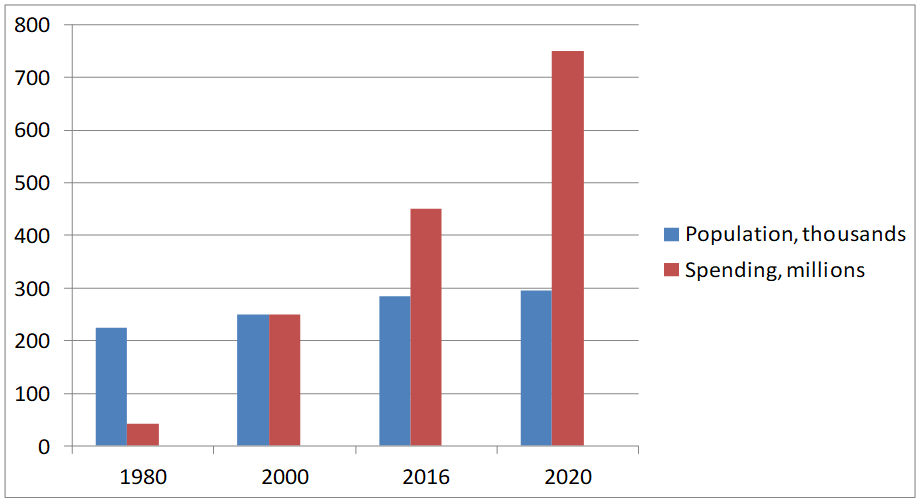

Fig 1: Barbados population; recurrent Health Spending 1980-2020.

Data obtained from annual CMOs reports (up to 2012), annual budget presentations. The annual CMO has not been available after 2012.

If one looks at the trend of Barbados’s population growth and government’s recurrent health spending in the period 1980 to 2020, one can see that the recurrent health spending has risen (and continues to rise) at a much faster rate than the population growth in this period. This trend of increased recurrent health spending is occurring while the health situation seems to be getting worse, not better. It would take someone with a massive amount of optimism to project that the Government can continue spending on health in a way it has done in the past, and that this will lead to an improved local health situation.

So it can’t (or shouldn’t) be business as usual in health. Our profile of health illnesses, i.e. mainly the Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) suggest that we should focus on tackling the issues from the front, we must focus on early diagnosis and early intervention. We cannot build an Emergency Room and hope to save everyone who comes in with a life-threatening complication. With our health profile, we cannot sing “Don’t worry, about a thing”, and hope that “Every little thing is going to be all right”. We cannot keep kicking the can down the road.