Dr. C.V. Alert, MB BS, MSc, DM.

Family Physician.

Is our health care any good?. Is it horribly bad? The answer depends on your vantage point, and what parameters you use to evaluate the health care.

In the ‘good old days’, at least up to the year 2012, the Chief Medical Officer (CMO) produced and released a CMO’s Annual (Health) report, which gave some statistical data on the happenings in Barbados, specifically what is happening in the public health services. This CMO annual report suddenly ceased after 2012, although there was an attempt to resuscitate the CMO’s annual report in 2019 with the release of a one-off report called “The Barbados Health Report 2019”. Again, after this attempt, there has been limited availability of national health data to the general public, or even medical professionals here. Fortunately, organizations such as the Barbados National Registry for Chronic Diseases and Cancers have released some local data on the NCDs and Cancers to the general public, but overall data on the performance of our national health institutions has not been made available to the general public.

While the Queen Elizabeth Hospital (QEH) is in the news very often, little formal evaluation of the hospital on a whole, or of any of its many departments, has been released to be public, so hospital services, essential as they may be, are hard to evaluate. We had reasons to be optimistic about transparency in the QEH services when, at the turn of the century, the government appointed a Commission chaired by Sir. Richard Haynes to evaluate some of the services at the QEH, in particular the Accident and Emergency (A&E) Department. This commission, for example, enumerated the number of staff in the department, the number of patients who passed through the department, and the average waiting time the patients experienced.

It was hoped that this data would help to rationalize, and subsequently improve, the services offered. But this model seems to have been abandoned. Many millions of dollars have been spent, facilities have been expanded, staff numbers have been increased, yet the actual service and waiting times has worsened. The hard data has not been offered outside of the Ministry of Health (and Wellness), so the increased spending cannot be analyzed. Are cost-effective decisions being made, are millions of dollars being wasted, or is there any effort to evaluate the spending? It also means that we cannot discern the direction in which our health is headed.

This is occurring at a period in time when the Ministry of Health and Wellness has earmarked the introduction of electronic health records (EHRs) in the polyclinics and the Queen Elizabeth Hospital, from around 2012. In theory this should mean access to real time data on our health situation should be easily and readily available, with the click of a mouse. In practice this is not the case.

But Covid -19 is not the only new issue that has arisen in recent years. In 2016, for example, the then Minister of Finance introduced the ”Sweetened Beverage Tax”, a tax primarily on sodas designed to reduce their consumption, fearful of the relationship between these sweetened beverages and type 2 diabetes mellitus. There has been different views as to whether this 10% tax was/is effective, with the soft drink manufacturers claiming that the measure has had limited effect on their sales, some health professionals saying that the tax is working, and some health personnel calling for even higher level of taxation.

But some beer manufactures also saw this new cost of sweetened beverages as an opportunity to introduce “4 for 10” campaigns [Four beers for ten dollars]: sudden the price of a beer was similar to the price of a soda. But what did this do to the consumption of beers, in a land where alcohol consumption is still associated with a non-insignificant number of psychiatric and medical illnesses, including hospitalizations at our main Psychiatric Hospital and the QEH, and road traffic accidents. Data that should be available in a CMOs report should allow us to see the direction of sweetened beverage and alcohol consumption, and the ‘health costs’ associated with their consumption.

Our Health care is good!

When compared to our Caribbean neighbors, some of our health statistics look great.

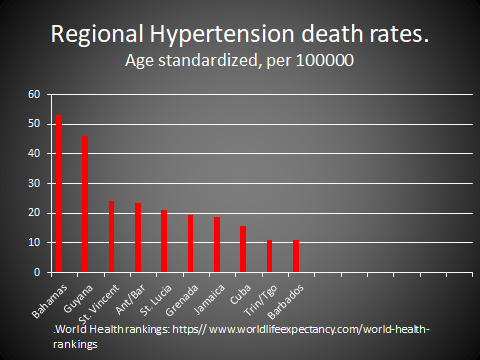

Data from worldlifeexpectency.com, an online source that follows in real time many common disease patterns in almost 185 countries around the world, shows that Barbados’ death rates rank favorably when compared to our Caribbean neighbors. The chart shows the picture with hypertension, but the diabetes picture is very similar, and these are two major diseases that affect Caribbean people.

What do local consumers think?

- A recent local Whatsapp video spoke of a patient who went to the A&E Department of the QEH, and had to wait 3-4 days (72-96 hours) prior to being seen by an Emergency Physician. The quick response by the acting Minister of Health and Wellness stated that official investigations into the Department suggested that the ‘average’ waiting time was closer to 30 hours. Mathematically, an ‘average’ of 30 hours certainly suggests prolonged waiting times in an Emergency Department, and does not exclude individuals having to wait as long as long as 96 hours, as the circulating video suggested. An Advisory from the QEH released on 9/19/2023 suggests that even these waiting times are likely to be increased, based on demands made of the department. Is this acceptable after all the millions of dollars spent on health care (see below)?

- Many callers to our radio stations have, over many years, spoken of problems assessing care in both our polyclinics and the A&E Department. This has been occurring in spite of enlarging the A&E Department, and increasing the emergency access times at some polyclinics. Meanwhile, in the private health care sector, there has been an explosion in the number of Emergency Clinics. To date, there is no evidence that focusing on emergencies, as opposed to ongoing care, leads to improved health outcomes, here or anywhere else.

- What doesn’t help build confidence is the untimely ( and often indefinite ) cancellation of appointments in the public system, leaving patients without critical medications, appointments and sometimes operation dates, with no clear-cut idea of if/when these untenable situations would be satisfactorily resolved.

- In the CMO’s report of 2006, it was noted by the bed occupancy on the Medical Wards at the QEH was 120%. In early 2021, the CEO of the QEH noted that the bed occupancy on these same wards was 200%. So that there is chronic (and increasing) overcrowding of the medical wards in our main tertiary hospital, the QEH. There has been some public conversation on the need for a new General Hospital, but perhaps the conversation should also include increasing our efforts at ‘Health Promotion and Disease Prevention’, specifically when the NCDs are amendable to this type of intervention. This conversation should include improving our primary care services, i.e. the polyclinics, to reduce the load on the QEH.

- No formal analysis of our polyclinic services has been offered, yet they can serve as important gate-keepers for our national health care services. Outside of the hospital, our appetite for fast foods and sweetened beverages, coupled with our disdain for regular exercise, is fuelling our rising obesity prevalence. Once obesity develops, this generates heart attacks, strokes, kidney failure and a variety of cancers, and these fill up the QEH. There are even associations between obesity and a variety of mental disorders. So should we fatten up our people, and build bigger hospitals, or focus on preventing obesity by promoting better diet and exercise habits?

Our Health Care is bad.

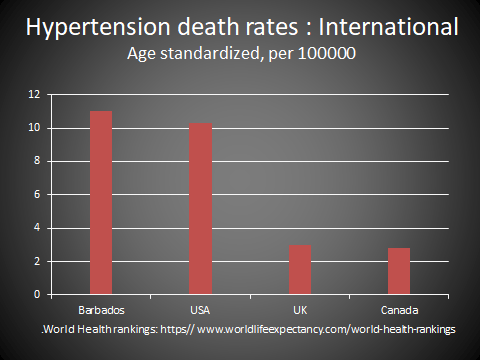

When compared with the UK and Canada, for example, our hypertension death rate is many times higher. This was also true two decades ago, when Sir George Alleyne, then Director of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), pointed this out to Caribbean Heads of Government, and was perhaps a factor that led to the ‘historic and unprecedented’ 2007 conference in Port-of-Spain, Trinidad: “Uniting to stop the epidemic of Chronic NCDs”. Caribbean Heads of Government and Ministers of Health agreed on a series of mandates at this conference, and reflected on commitments to action in key areas.

So the perspective, at least back in 2007, was that Caribbean health care was bad, and required a bold initiative by Caribbean leaders to ‘turn the ship around’. More than two decades later there has been microscopic progress in fulfilling these commitments, and many subscribe to the view that the health care ‘ship is sinking’.

How come our hypertension death rates are so bad, when individuals here have free access to medical care and free access to a variety of anti-hypertensive (and other chronic disease) treatment medications? Our Barbados Drug Service spends millions of dollars in purchasing these drugs. We hear of the horrendous costs of medications in the USA, for example, with persons having limited access to medical insurance (in spite of the best efforts of expanding the Affordable Care Act (Obamacare)), and people going into bankruptcy because of medical bills, but we do not have a comparable issue here. We have great weather year-round to encourage physical activity, an important part of health promotion. Feeling all-right may not be the same as being all-right, but far too many persons only respond to an ‘accident or emergency’, thus creating the backlog at the A&E Department. In far too many cases this response is ‘too little too late’.

Health, Wealth and Happiness.

The combination of health, wealth and happiness is a desirable combination, but it is unclear how often these actually occurs, or even how to accurately measure each individual component.

At a national level, we can identify where some financial resources are tied up with health.

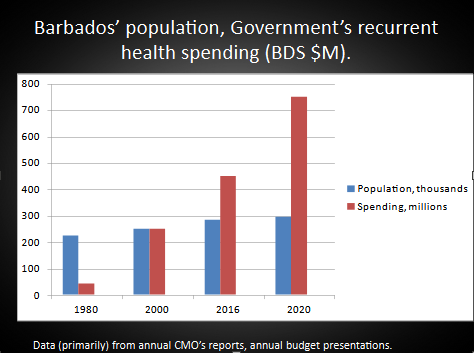

When one looks at the trend in Barbados’ population growth and recurrent health spending over the last 40 years, one can see that the health spending is rising much faster than the population growth. When one compares 1980 and 2020, for example, while the population growth has been approximately 27%, the rise in recurrent health spending has been 837%. This is largely due to major rises in health care costs in the intervening period. But over the years there have been many observations that our present model of health care financing may not be sustainable, and both of our major political parties have held town hall meetings on health sector finances reform, with “NATO – No action, talk only” being the end result.

The figures for health spending in the private sector, including spending by medical insurance companies, are not readily available. However, available evidence suggests that many people are unwilling, and some unable, to afford private medical care. The disease profile also suggests that many people don’t realize that an ounce (or gram) of prevention is better, and far cheaper than a pound (or kilogram) of cure. Some effort, and significant monies, is being spent treating established disease, while efforts at disease prevention are more likely to be successful.

With a few local clinical audits done over the years consistently showing deficits in our primary care services, albeit with limited involvement of our private primary care services, perhaps it is time for a a forensic audit of these services, but only if followed by a meaningful intervention. This audit has to look into whether our health care workers have adequate and appropriate training, resources and supervision, to face the challenges of the NCDs and the tsunami of infectious diseases projected to target the world in the next few years. Poor service is poor service, even though the ‘consumer’ is not charged at the point of service. Poor service is poor service: while we are at least as bad as any other Caribbean country, we rank (again using hypertension as an example) around 126 in a comparison of around 183 countries. But Caribbean and International rankings apart, look as the negative effects within Barbados, where our hospital wards and A&E Department are busting at the seams, and our health spending has taken off like a short pitched bouncer. So take your pick: are the millions of dollars being well spent?

There are many facets to Health Care, and in some areas Barbados may be very good, and perhaps not so good in other areas. We look forward to resumption of the annual CMO reports, so that an evidence based assessment can be made of our local health services. [The University of the West Indies (UWI) in Trinidad has a Health Economics Unit, so expertise in this area is not far off]. Optimistically, this may stimulate action by our Health Decision makers, who appear to be ‘stuck in neutral’. It would also allow an assessment of the direction of local health, while health care spending rises almost exponentially. Evidence-based decisions, followed by monitoring, may help our decision makers to make cost-effective decisions that offer the opportunity for improved patient outcomes.

The MOHW has held health data close to its chest. In the meantime the snapshots we are getting of our health point to a picture of us struggling to stay on top of the situation. Effective communication is an important strategy for building thrust between our Health Decision makers and the general public. We hope that we don’t have to wait until files ‘fall off the back of a truck’ for a true picture of total health to emerge, and to develop comprehensive strategies, based on research, to reverse our apparently deteriorating national health.